Adriana Bravo and Laura Navarro

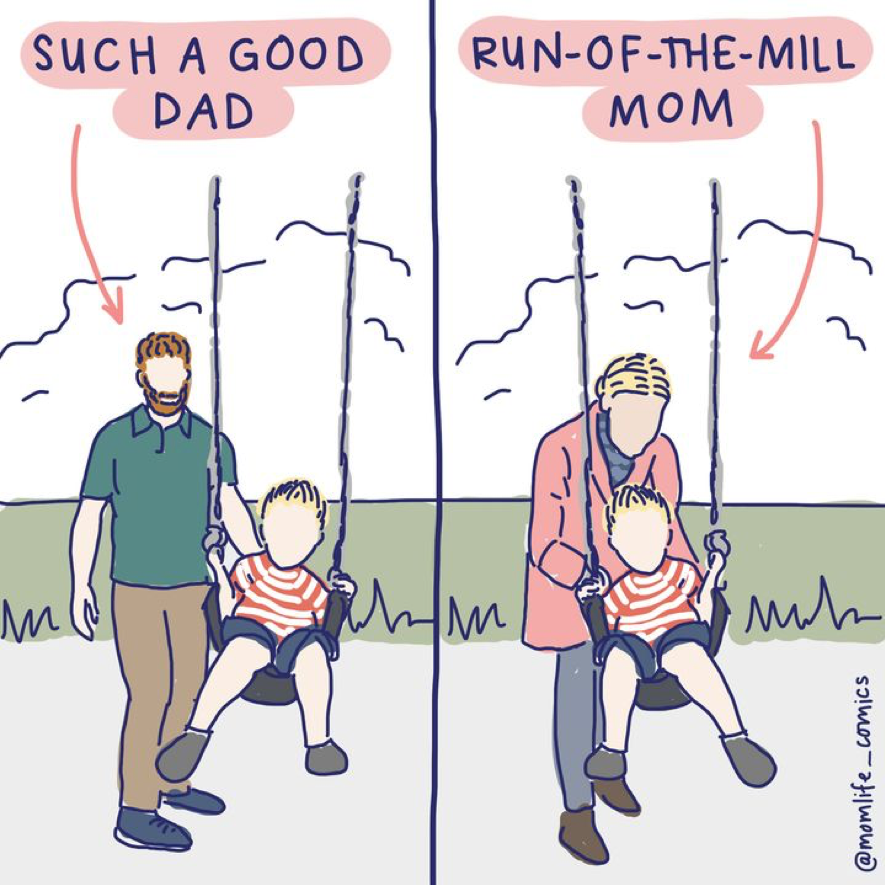

In the following entry, there is a discussion of the gendered social expectations that mothers face and how online communities have been challenging them by providing them a platform to express their feelings and concerns.

1. INTRODUCTION

For the present paper, we will analyze how numerous modern discourses have shifted the view on gendered parent responsibility. This subject is particularly relevant since the expectations of both motherhood and fatherhood not only have differed historically but, to this day, they are still being debated and rewritten affecting the current reality of parents. What are the dominant discourses of gendered parenthood, and how are online spaces for mothers challenging them? That is the issue we will attempt to shed light on by questioning how webpages/forums such as Mumsnet help challenge gendered parenting discourses, the constructed expectations therein, and how they reflect the shift in modern gender-specific parenting expectations that has occurred.

Firstly, we will begin by establishing the theoretical framework that has allowed us to analyze and identify the various – and subtle – gendered stereotypes and discourses surrounding parenthood. We will present the findings and key concepts we have extracted from the articles that have allowed us to better analyze our object of study. As for the data and methods section, we will review the online post we have chosen to analyze and the different aspects we will explore, alongside our reflection on the study. In the results section, we will provide the evidence we have found during our linguistic analysis of the post. Finally, we will attempt to answer our research question in the Conclusion section, with our concerns and possible future research directions.

2. THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

To understand the current social events and changes in parenting we will situate our analytic viewpoint within Postmodernist Feminism since it has vastly influenced the vision of gender and performativity during the last decades of the twentieth century and still permeates our societal consciousness during the twenty-first century.

In Feminism is for Everybody, Bell Hooks (2014) discusses feminism in different life areas. We have narrowed our perspective by focusing on two chapters, Feminist Parenting and Liberating Marriage and Partnership. In the former chapter, we can find a contemporary perspective on the impact of feminism on parenting, such as a newfound expectation for fathers to be more involved. In the latter, Bell Hooks (2014) discusses not only the patriarchal views of female sexuality and how it is male-dominated in heterosexual marriages but also how the gendered expectations for parents are still present even more when it comes to who should be the working parent versus the “stay-at-home” caretaker.

Mackenzie (2018) analyzes the discourse around gendered parenting in online forums and communities by examining a thread written by mothers on the blog Mumsnet. Mackenzie’s research begins by establishing how discourse strongly shapes identity construction, “[t]his means that our sense of who we ‘are’, what we know, and the power to define that knowledge and subjectivity, is discursively regulated” (Mackenzie, 2018, p. 116). This assertion creates the baseline for her study of the thread, which concludes with her establishing the three dominant discourses on mother identity and one for parenting: “Gendered parenthood” (the notion parents have different responsibilities depending on their gender), “Child-centric motherhood”(the idea that children should be at the center of a mother’s life i.e. her only priority) “Mother as a main parent” (the belief that the mother inherently has more responsibility as a caregiver because of her gender); and a fourth discourse titled ‘Absent fathers’(Regarding the figure of a father who takes little to no part in his children’s care).

Finally, we have drawn on Rashley (2005) which examines parenting websites as a source for parents, to find information and community, specifically, she dives into the apparently progressive platform BabyCenter. However, as her analysis progresses, there appear to be numerous instances that signal that BabyCenter might promote traditional parenting roles disguised behind a progressive façade such as the amount of resources targeting primarily women and mothers when it is a forum for both fathers and mothers, the focus on heterosexual couples, women and mums as the ‘glue’ of the family, and the blame and prejudices held onto single parents.

3. DATA AND METHODS

For the current research, we have chosen a medium to long post (216 words) from the online mums’ community/thread website Mumsnet. This post is authored by a mother who shares with the online mum community her pain and despair about the fact that, since her husband left her, he has taken little to no responsibility in their children’s care.

In this text, we will analyze the different themes and discourses uncovered by the different linguistic resources such as the presence or non-presence of determiners, possessives, the different uses and connotations of the lexicon, or the verbal aspect. We will carry out our analysis following a linear analysis – that is, we will begin by analyzing the title and then move on to the parts we have identified in the post for the linguistic analysis (background information (l. 1-5), issue (l.5-12), laments (l- 13-15), and the complaint (l. 15-16)), and finally, we will later proceed to the analysis of discourses.

During this project, we had different expectations of what our findings would be. On the one hand, there were anticipations for a more traditional scope in a few of the discourses found that supported the notion that mothers should carry more responsibility. However, we were pleasantly surprised to see that there is a lot of feminist rhetoric striving for equity, even recognizing the stereotypical and patriarchal roles that may appear nowadays disguised with progressive language. Nevertheless, we did expect to see a bigger change in the contemporary perceptions of gendered roles for parenting since feminism is something that most young parents have grown up with. Hence, our surprise was to realize that the traditional patriarchal view still prevails, that just the form of the words in which the message is conveyed has changed. Also, we found it difficult to uncover some of the discourses since they are well-integrated into our societal belief system. Overall, what we have learned is that there is a gigantic structure surrounding prevalent social norms and that we need more than ideas to shift them. Clearly, we might think we have progressed regarding other times – and in some aspects we have – but we still reproduce some notions we thought we had already moved on from, and we do it unconsciously.

4. RESULTS

As we analyze the post from Mumsnet, we can observe how the different discourses surrounding gender affect present-day parents. Already, in the title, we can observe one of the categories Mackenzie establishes – child-centric motherhood – when the writer of the post (from here on referred to as OP i.e. “original poster”) begins declaring she loves being a mum, and a single one now, ‘but…’ Since women are expected to devote themselves to their offspring and to lose themselves to love them, she feels the need to begin declaring that she actually loves them, she loves her life yet there is still a ‘but’. This case also relates to gender expectations and the fact that women’s natural and sole/primary purpose is nurturing and caring for their kids (which relates to Mackenzie’s category of ‘mothers a main caretaker’). She cannot complain straightforwardly about her situation because that is the “purpose” of being a woman: to love and take care of your kids. Hence, she decides to introduce and reiterate her love for her children before introducing the “but”. In doing so, she minimizes any potential backlash she might receive from straying from the dominant discourse.

In Rashley’s article (2005), we encounter how single parents, especially mothers, are faced with judgmental attacks and hostile replies, as she explains, “[the mother’s] plea for understanding is certainly not an uncommon one in the community spaces in [BabyCenter], given the site bias towards women involved in financially stable partnerships.” (Rashley, 2005, p. 79) And although Mumsnet seems to be a safe space for mothers, even in apparent ‘safe spaces’ single mums cannot escape the societal judgmental attitude towards them. That is why OP also pleads for understanding: she is going to complain about her situation but she still feels the need to justify herself by stating that she loves her kids. This fact might be due to, according to Rashley (2005), the fact that women are perceived and expected to be the glue that holds the family together (p. 61); hence, she might be looking for understanding rather than blame for her situation.

- Linguistic features

In OP’s post, we can observe how lines 1 to 5 give background data on her situation, which constitutes the “orientation” portion of her story following Labov and Waletsky’s (1697) structure of “Narratives of personal experience” as seen in Caldas-Coulthard (2013). This structure suggests that there are a few distinct parts that constitute the structure of the retelling of personal experiences, those being, abstract, orientation, complicating action, evaluation, result, and coda. In this case, OP is using orientation, which “sets the scene: the who, when, where and what of the story. It establishes the ‘situation’ of the narrative.” (Caldas-Coulthard, 2013)

| “Husband left family last Christmas – having an affair – loved the OW and hated me to summarise. Nearly destroyed me in the process blaming his affair on my shortcomings so much so I literally couldn’t see what he was doing. Through therapy I have realised this was abuse and I’m moving forward without him. We have two beautiful children, five and two and this is where the issue lies.” (OP, 2023) |

In the first sentence (l. 1-2) there is a lack of determiners, possessives, and deictic elements, she is using a rather straight-to-the-point language that provides a sense of rapidness and detachment, and she only conveys the necessary background information for the reader to understand. This might be because she no longer identifies that man as a part of her family but only as the progenitor of their common offspring since she later uses ‘we’ (l. 4). In the next lines, though, there is more presence of possessives – she is assigning roles more clearly – as in line two when she properly labels the affair as ‘his affair’ or that he blames said affair on ‘my shortcomings’ (OP, 2023). From now onwards, since the mother begins identifying the situation more with herself, there appears to be more richness of linguistic elements, such as the ones mentioned above. The presence of aspect – perfect (such as ‘realised’ in l.3) and later progressive (‘moving forward’ in l.4, for example) – offers a sense that it has been a recent finding that her ex-husband emotionally abused her by placing his blame on her. The underlying message she is exposing then is, as Rashley (2005) explained, society’s belief that women are entirely responsible for the family; even when the familial unit fails for other reasons (such as the husband having an affair), it is still her fault. This notion of blame will reappear also in line 13 where the notion of blame is expanded. Furthermore, in line three onwards, OP also uses the first-person singular ‘I’ assigning herself a role alongside the presence of the progressive aspect to refer to her current situation (she is healing, is progressing without him), which might allow the reader to empathize with her; therefore, they will not blame her for her failed family. Moreover, in line five, she appeals to a compassionate ear by transgressing only one norm: single mother. She does this through the manner she describes her children (which will be recurrent in the different parts of the post). In line five, despite having complaints, she describes them as ‘beautiful children’ (l. 4). This more heart-warming description aids her positioning as a loving and nurturing caregiver. She also uses abbreviations that are within the lexicon of “online vocabulary” that is immediately understood by her community. Using OW (“Other woman”) to refer to her husband’s affair partner creates a sense of closeness and familiarity among the users because of the feeling of “speaking the same language”(Mackenzie, 2018).

Furthermore, if we take the language she uses to describe her standpoint – as opposed to her ex-husband – we can see that within the first four lines, she establishes her husband’s character as someone who “hates” her (as opposed to the “Other woman” whom he “loves”) (l.1), whose actions have “destroyed” her (l. 2) and how she realized they were “abuse” (l.4). These verbs are meant to create in the reader an immediate sense of rejection for the ex-husband and make us empathize at the same time with the writer, as we see all that has been done to her within such a short period of time. Another instance of strategic vocabulary, used to appeal to the sympathy of the reader, we found might be the fact that she uses “Christmas” to establish the time in which her husband left instead of saying “last winter” or “last December”, which appeals to the compassion of the reader in a major way because Christmas is traditionally a holiday that is spent with family. Therefore, she chooses to emphasize the fact that the husband left her and the children during that time. Finally, going back to Labov and Waletsky’s structure, we see that she ends this paragraph by saying “This is where the issue lies” (Op, 2023) and thus she is establishing the “complicating action” part of her narrative, which is the one that “ answers the question ‘what happened’ ” (Caldas-Coulthard, 2013) and “brings in the elements which disrupt the equilibrium which will be finally restored by the resolution” (Caldas-Coulthard, 2013)

In lines 6 to 12 OP explains the issue,

| “Since the separation, he only wants to see them in the daytime although will frequently keep them out until after 7pm but then leave them home tired and over stimulated for bedtime. Overnights have been tried but three times now he has brought them home at 10pm in their pyjamas saying they wouldn’t settle! I am absolutely happy to have my children in their own beds: that is not the issue. The issue being is that is just sees himself as someone who takes them out for while and I do the parenting.” (OP, 2023) |

In these lines, we see how the writer describes her ex-husband’s actions with their children. At the beginning of line 6, she chooses to strategically frame her narrative with the phrase “Since the separation” (l. 6), so that her ex-husband’s actions appear as they are: his alone and by no means condoned by her. Then, she proceeds to use verbs such as “keep them” (l. 7) or “leave them” (l. 7) to describe his actions toward the children and paint them in a disapproving light. In lines 8-10, she chooses to add that her father took the children back home because they would not settle down for the night, and uses exclamation to convey her outrage to the reader and engage them to disapprove of such actions as well. By contrast, she uses adverbs to add emphasis when stating the fact that she is glad to be with her children by stating that she is “[a]bsolutely happy” (l. 10) instead of just “happy” which, when compared to the previous lines, seems to settle once and for all that while her husband is the one “leaves” them back at home she is the one who is thrilled to have them. Another point to be made here is the fact that the writer says that when the children are at her home, those are their “own” beds (l. 10-1). Painting a picture of her home as their “own” conveys a sense of safety and familiarity that would then contrast with the “strangeness” or “otherness” of the spaces related to the father. There is also added contrast if we take into account the fact that the father decides to take the children back to the mother’s place at night when they become more “challenging” and difficult to settle for him because they are tired, leaving the responsibility to handle their more “difficult moods” entirely up to the mother.

This is a point that culminates in line 12 with her positioning herself as the “parenting” party and her husband as “someone who takes them out” (l. 12). This self-identification with the parental role has also to do with the fact women are perceived as the primary caregivers who are expected to do all the parenting. This stands even during legal processes in which, after divorce, in a heterosexual couple the woman is more likely to have the children the majority of the time since she is “the mother”.

From lines 13 to 15, we encounter how the OP laments and evaluates the situation, while sharing a moral message with her audience when she states “ I feel so sad for us all as I just didn’t see this being my children’s life”. This message, taking into account the aforementioned Labov and Waletsky (1967) narrative structure would be included in the “evaluation” portion of the story, which, along with the orientation portion, is “a very important category in all kinds of narratives” (Caldas-Coulthard, (2013). Here she is expressing her disapproval of Husband’s actions since, morally, he should want to be more involved in their children’s care and instead he “frequently asks to keep them later and later but won’t do overnights, early mornings.” (l. 13-5). In other words, although the theoretical discourses surrounding parenthood have changed, in practice, many parents still approach parenting with a traditional gendered scope. We find interesting the use of the lexicon and the images evoked in the reader. She wants us to feel her despair because she did not expect this outcome when she was planning her future in a heterosexual family unit. OP uses ‘so’(l.13) with an emphatic role to remark how saddened she is because of the current situation. Again, we do not know how the father feels about the situation, yet the question still exists as to whether the use of the pronoun ‘us’ (l. 13) still includes him or not. Although she accepts how things have ended and moves on without him, she still performs the traditional role of the woman (in the sense that, traditionally, women’s core value has been their family and the success of it, that is, their essentialized stereotypes). Again, there is a stinging tone when referring to him, he is Husband (without determiners or possessive), yet she does not denominate him as ‘ex’ or ‘my ex-husband’. She resents him because, as OP mentioned before, she is doing all the parenting (including taking care of her children during nighttime and early mornings, not only when it is convenient), implying that he is not a ‘real’ father. It is relevant to note how she is saddened not by what has happened to her but because of how her children might feel about the situation (l.13). Again, she portrays a selfless image of the traditional woman: she only cares about how this unequal parenting situation might affect her children, rather than how her husband has failed her not only in their marriage but as a co-parent too. Unintentionally, she is appealing to us to pity her since she is the best co-parent, due to her devotion and caring, but fate has not done her justice. This idea is constructed when she adds statements to her discourse such as “I am absolutely happy to have my children” (l. 10) or “I just feel so sad for us” (l. 13), showing empathy not just for herself but for her children as well.

In the closing lines, she finally expresses her feelings and emotions regarding the situation, “It’s just irks me that some people think it acceptable to just throw in the towel when it comes their responsibilities” (OP, 2023. l. 15-6). She expresses her disconformity indirectly: she does not address her husband, instead, she uses the expression ‘some people’ (l. 15) to include him there. Similarly, she positions her kids and family as ‘responsibilities’ (l. 15-6). Traditionally, women are expected to be submissive and passive, hence, it is an undesirable trait to see a woman, even more a mum, look for confrontation. Therefore, she has to disguise her bitter feelings if she wants support and sympathy from the audience. She is also moderate with her language. For instance, instead of using harsher words, she opts for ‘throw in the towel’ (l.15-6). She equates herself to her husband in the parenting role yet he does not see it this way. That is what hurts her the most in her moral evaluation of the narrative.

Discourses

As established before, we will use Mackenzie’s discourse classification (2018) to identify the different discourses. The writer of the post denounces the fact that the father of her children had brought them back home several times when it was his turn to have them overnight (l. 6-10). Here, we can see how postmodern feminist discourse on parent responsibility has shifted the perspective of mothers from believing that they should be the primary caregivers and calls for father accountability. As Rashley states in her article, the role of fathers “has indeed changed enormously in recent years. Fathers are expected to be more engaged with their children and involved with housework—if not nearly as much as most women would like, certainly far more than the past generations of fathers would have thought possible” (Rashley, 2005).

Another example is how the mother reiterates things such as “I am absolutely happy to have my children in their own beds” (OP, 2023, l. 10), and, in another comment, she added later in the thread, she affirms that being a parent is “the most important thing [she does]” (line 2, update 1). These statements could be argued to be closely related to Mackenzie’s discourse on child-centric motherhood. While the writer of the post seems to agree with the idea that the father should be more involved, mothers still seem to fall at times victim to the traditional notion of the “good mum”. As stated by Mackenzie, “[this does] not only position women in relation to children, as ‘mothers’, but evaluates them in relation to their successful adoption of this subject position” (Mackenzie, 2018, p. 124). While great strides have been made in communities such as these to assure modern mothers that parenting should be divided equally, as Rashley argues “[w]e cannot ignore the fact that the core of our assumptions about parenting —the mother’s responsibility— will not automatically or immediately change with it as that culture is moved online” (Rashley, 2005, p. 85). Thus, we may still find remnants of traditional gender roles when it comes to parenting for quite some time, as we do in this individual post from 2023.

As for laments, the writer states “I feel so sad for us all as I just didn’t see this being my children’s life” (line 13). While it is common for mothers to feel disheartened by the situation of losing not only a partner but also a co-parent, this statement could also denote potential feelings of guilt in the mother. As Bell Hooks states “Many people assume that any female-headed household is automatically matriarchal. In actuality, women who head households in patriarchal society often feel guilty about the absence of a male figure” (Hooks, 2014, p.72)

Finally, we believe that the real issue behind the post lies when the mother states that she is concerned because the father of her children “just sees himself as someone who just takes them out for a while, and [she does] the parenting” (lines 11-12). This perfectly exemplifies Mackenzie’s discourse on the fact that mothers are perceived to be the “main parent” (Mackenzie, 2018). This perception is precisely the writer’s issue with her husband’s behavior. She resents the fact that, as she argues, he just would “throw in the towel” when it comes to his responsibilities as a parent.

5. CONCLUSIONS

We can conclude that the feminist literature and its ideas have permeated into the individual’s discourse resulting in discussions in online communities that keep contributing to transform the dominant narrative by presenting parenting as an equal task between both caregivers. Nevertheless, there is a prevalent attempt to perpetuate traditional patriarchal discourse since it is still integrated into the collective mindset, which is why there are still cases, like OP’s, where nothing seems to have changed. Still, our view on this matter is somewhat limited to the online community we have sampled and the studies available to us at this time. Thus, as new literature emerges and the culture of gendered parenting moves forward, this topic will continue to be an ongoing debate.

6. REFERENCES

Caldas-Coulthard, C. R. (2013). ‘Women who pay for sex. And enjoy it’: Transgression versus morality in women’s magazines. (pp. 258–278). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203431382-21

Hooks, B. (2014). Feminism is for everybody. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315743189

Mackenzie, J. L. (2018). ‘Good mums don’t, apparently, wear make-up.’ Gender and Language, 12(1), 114–135. https://doi.org/10.1558/genl.31062

Rashley, L. H. (2005). “Work it out with your wife”: Gendered Expectations and Parenting Rhetoric Online. NWSA Journal, 17(1), 58–92. https://doi.org/10.2979/nws.2005.17.1.58

7. PRIMARY SOURCE

https://www.mumsnet.com/talk/relationships/4965770-i-love-being-a-mum-and-a-single-one-now-but