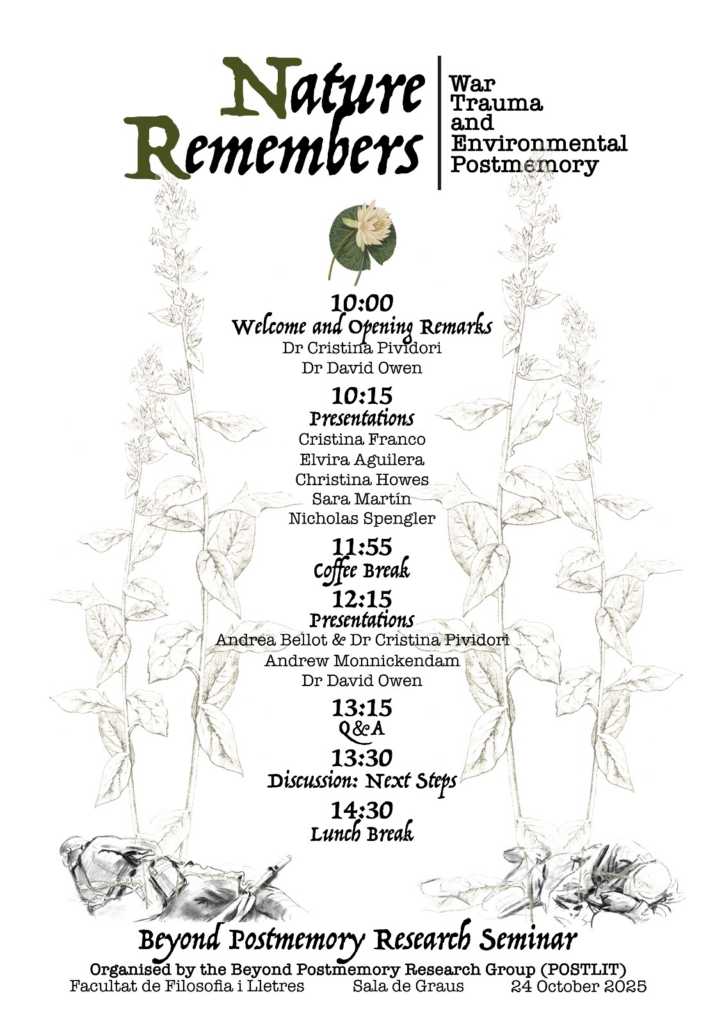

Poster and Reflection: Beyond Postmemory Research Seminar: “Nature Remembers: War, Trauma and, Environmental Postmemory”

The intertwined relationship between nature and memory has been denied for a long time. A shift in perspective is currently replacing the anthropocentric storytelling with a richer viewpoint, one in which nature moves from the background and takes the spotlight. The recent recognition of natural entities, rivers, seas or forests, as ‘legal persons’ can be seen as a major development in how we understand our relationship with the natural world.

Human actions have both intended and unintended consequences on nature, which bears the scars, the footprints of human conflicts. The intentional or accidental destruction of land, fauna and flora reshapes the terrain, leaving marks in the topography, while the memory of what once was becomes an agent of the past. Communities and individuals trace their histories through these agents. Even when a displaced or disappeared community can no longer tell its own story, or the story of its land anymore, memory can still be traced in the land itself, for example through the movement of species or the residual effects of materials in the area.

Nature and environment have been relegated to the background or to a symbolic role in literature too. New readings have opened the door to new interpretations of old stories, allowing us to reconsider our relationship to the land, or even to imagine the land independently of human intervention. While recovery, often related to human hope, is possible, dystopian and post-apocalyptic scenarios highlight a very contemporary fear: that once trespassed the threshold of destruction, recovery may no longer be feasible. This is, in the words of Sara Martín, a ‘Zero Ecology’ situation.

The submitted graphic pieces intend to reflect these considerations. The choice of subtle sketches blending into the white of the page illustrates the delicate and intricate interplay among the elements central to this task: nature, war, memory and literature. The war scenes, a fallen soldier and a destroyed landscape are based on studies by the American artist John Singer Sargent, who illustrated scenes from World War I. The plant illustrations are the work of the American botanist and illustrator Charles Frederick Millspaugh. In some sketches, most elements are faded, in others, the natural element is highlighted in colour, representing the current stance on the importance of nature within literary studies. Finally, the choice of the blank page and minimalist typography intends to recreate a book index.

Follow-up Report: Beyond Postmemory Research Seminar: “Nature Remembers, War, Trauma, and Environmental Postmemory”

The literary studies of Postmemory are based on three core models: the Performative, the Transcultural/Transnational and the Imagine model. A fourth dimension to explore corresponds to the Material and Environmental Memory. The Seminar Nature Remembers explored this dimension in its members’ most recent articles.

A new inspection of nature in contact with humanity stresses the relationship between a physical or material environment, and memory. Cristina Franco highlights that contact through Michael Cunningham’s Day (2024). In the novel, the natural and human worlds mimic themselves forcing the reader to rethink the real role of nature as a rebellious force instead of an ideal and traditional shelter. Death and grief are part of a liminal space where humans become aware of life fragility, an amphibious state where the arrival of death reveals nature and human connections as we recognise nature’s ability to communicate. Nature is a sentient agent of memory.

Agency of memory is not just a lieux de memory but the acknowledgement of a reciprocated interaction embodied in an agent. Elvira Aguilera remarks on the features of embodied agents in Hala Alyan’s Salt House (2017) through a phytosemiotic perspective. When the politics of others, the non-humans, are taken into account, a richer narrative of spaces and nature becomes intertwined with our own conflicts, displacement and nostalgia. Salt House goes beyond the memory activation via trees and fruits to consider the memory of a tree instead of the memory about a tree.

Nature is vital to memory but to assess how it is involved in violence requires to trace parallels between personal and global trauma. Christina Howes argues that an intersectional review of Richard Flanagan’s Question 7 reveals the landscape as a witness of violence. Furthermore, the book assesses a direct relation between harm and healing, between memory and responsibility. The process of healing begins when the ecological dimension of war and violence is recognised. This process requires responsibility and urges us to recognise our own diversity through other perceptions of the world, perceptions downplayed by the western civilisation, such as indigenous approaches to temporality and phenomenology.

Visualising the future, dystopic literature produces a fertile field of exploration for negative evidence: a world without an alive natural environment could reveal the inner human nature. Sara Martin takes Cormac McCarthy’s The Road (2006) as an example of a dead world where devastation externalises human nature. The dark perspective portrayed in McCarthy’s work seems to emphasise our current ecocriticism in times of climate change. However, the rebellious state of nature and its fight for survival is subtly displayed and Martín argues that a couple of symbols in the book serve that purpose.

A materialist approach is used by Nicolas Spengler as a way to convey the memory. Tracing parallels between Ocean Vuong’s On Earth We’re Briefly (2019) and John Akomfrah’s Vertigo Sea (2015), Spengler suggests that memory involves a non-human reframe of violence. The gruesome scenes of Vuong’s work depict memory as key to survival and violence as heritage for the future. Akomfrah’s visual art installation adds layers of selection to question what goes by the filter of our memory, pointing to the violence of exclusion and erasure of ‘the story we tell ourselves’. These two works and their juxtaposition of scenes illustrate Michael Rothberg concept of a multidirectional memory.

A multidisciplinary characterisation of memory is the approach taken by Andrea Bellot and Cristina Pividori to describe its intramaterial representation. Through the works of Lynn Nottage’s Ruined (2008) and Eve Ensler’s In the Body of the World (2013), theatre is a space of remembrance and confrontation, a space where the archive of trauma becomes a postmemorial work. Bellot and Pividori find correspondences between the violence against women in Congo and environmental violence. There, the body and nature carry knowledge, which turns into physical memory. In both cases an ethical approach is necessary for healing. A decolonised stance is required for ecological memory to return to earth.

The ambiguities of progress and tradition, such as the discourse of a ‘natural’ and simple way of life are represented in literature. Andrew Monnickendam explores these contradictions in the depiction of Ho Chi Min, ‘Uncle Ho’, in Duong Thu Huong’s The Zenith (2012) and the ambivalence of the Vietnamese leader’s mausoleum, a monument built to celebrate the figure of the strongman and the regimen he represents. The discrepancies between the humble house of the ruler and its heavy soviet style funerary monument epitomise the projection of a selective memory, a feature of a personalised collective memory.

Collective memory can be brought by means of re-enaction in an event as it happens with music. David Owen demonstrates this active remembering through the performance of Jamie Foyers, a traditional Scottish song. Owen argues that musical re-enaction differs from repetition in its transformative nature, its transcorporeal physical dimension, and its sonic geography. A generational aspect shapes the cultural longevity of traditional songs. Jamie Foyers’ ecological scars of mortality and loss become memory by virtue of a declarative action.

Knowledge transmission is a major issue in the research of memory. Members of the research group believe that an unorthodox style of presentations, such as the ones from David Owen and Nicolas Spengler, put in perspective the intersectional nature of postmemory research while opening the chance to explore how to translate the body of research to a publication. Finally, Sara Martin remarks the urgency of keeping the literary work at the centre of the research, supported by the frame but never overshadowed by it.