September 3, 2024 | Madrid, Spain.

By José Saturnino Martínez García.

What does the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA, by its English acronym) of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) measure? Its creators define it as the literacy (literal translation of alfabetización) of 15-year-old students in various subjects. This “literacy” can be understood as the ability to understand and apply in everyday life contexts skills in reading, mathematics, and science.

But to what extent can the development of this capacity be attributed solely to school? Learning occurs at school, but also in other life contexts. Reading competence can develop through leisure reading or role-playing games. Mathematics, through computer or board games. Science, by consuming scientific outreach or playing at experimenting.

PISA tests attempt to establish how much students learn in one year of schooling in each country, a concept they call the “one-year effect” or “efecto de un curso.” It is estimated using a series of statistical methods that I will explain below. But, as we will see, there is a risk that this estimation may be more of a statistical “artifact” than a substantive reality.

If it were true that the one-year schooling effect is 20 points, as derived from the latest PISA report, its main finding would be how little effective a school year is as a means to improve educational competencies. That is, students “become literate” or enhance their ability to apply reading or mathematics skills in real life largely independently of formal classroom teaching.

How PISA tests are scored

For the test results to be comparable between different countries, with varying educational systems and different curricula, the test is designed within the framework of a psychometric evaluation model called item response theory.

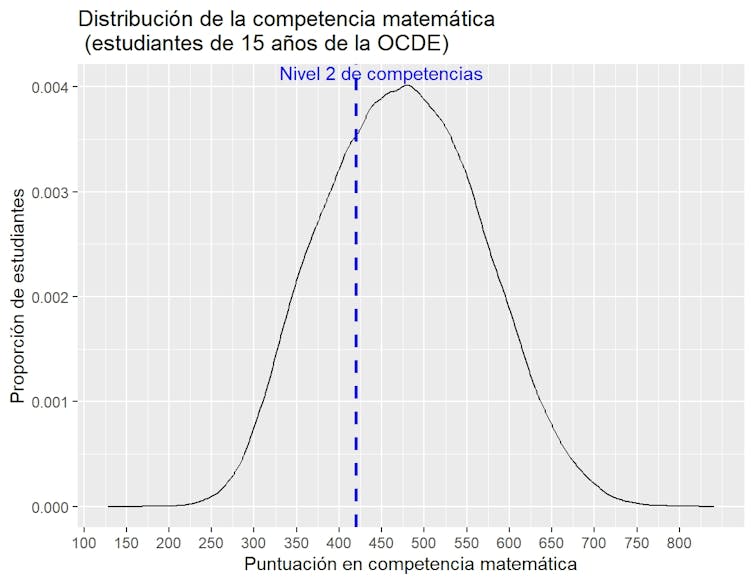

Scores are statistically calibrated with a “normal” curve (or Gaussian bell curve), which determines the mean and standard deviation. In the year 2000, for example, the mean was 500 and the standard deviation 100. Therefore, a 500 has nothing to do with a 5 on an exam: it indicates that approximately two out of every three OECD students score between 400 and 600 points.

How to interpret these points? The OECD has chosen to define eight groups and associate each with a competency level, in intervals of about 60-70 points. A result below 410-420 points, the lower boundary of Level 2, indicates that the student does not have a minimum of competencies to successfully face adult life to some extent.

One-year effect

The OECD proposes another strategy to give substance to these highly abstract figures: the one-year schooling effect. However, this poses a problem, as the test is not designed to study said effect, since it is only administered to 15-year-old students. What it does is compare students of that age who are in different school years.

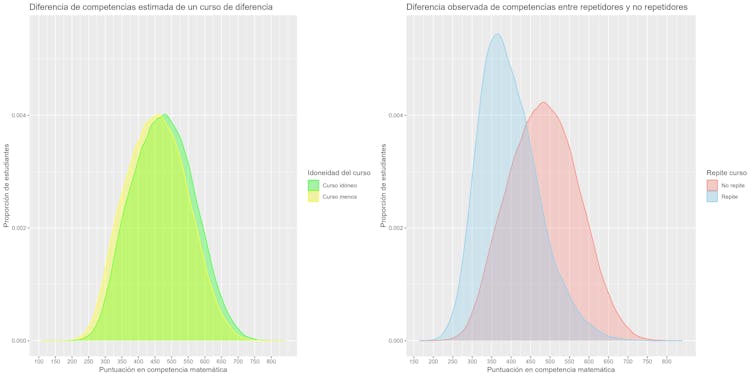

To estimate differences between one year and another, the OECD proceeds with a “residual” methodology, which consists of attributing to the effect of one year everything that cannot be attributed to other causes. A statistical model is designed with all the characteristics in which those in one year differ from those in another (social origin, migration status, and sex, basically), and the differences not explained by said characteristics are attributed to the year of schooling.

The procedure, therefore, consists of a statistical simulation, in which it is assumed that if two 15-year-old students, one in 4th year and another in 3rd year, are equal in socioeconomic and cultural origin, sex, and migration status (and the social composition of the school they attend), the differences between them are attributed to being in different years.

However, the report itself acknowledges that what one group of students and another are studying is not necessarily the same, as depending on the countries, they may be following different curricula (for example, in Spain, at age 15 one can be in different years: in different years of ESO, in Basic FP, or in the Learning and Performance Improvement Program until the 21/22 school year, when PISA is conducted).

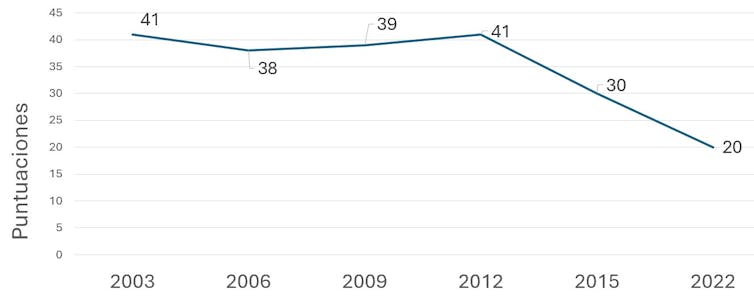

This “residual” method makes the grade effect variable, both by wave (or period in which the tests are conducted) and by country. The evolution of the estimated score in Spain has gone from about 40 points in 2003 to 20 points in 2022.

While the report itself (on page 165) warns that this score is specific to each country and wave, the 2022 press release summary does not take these warnings into account and presents variations between 2018 and 2022 in terms of “school years” (absurd, given that the effect size changes between waves). As a result, in public opinion—and even among experts—the idea has prevailed that in 2022, “20 PISA points equal one year of schooling” for all countries. To give us an idea, in other years where country-specific estimates are shown, in Spain, for example, 61 points are attributed to the school-year effect in 2012, while the OECD average is 41.

The Devalued Effect of One Year of Schooling

Twenty points is a small effect. When interpreting a small effect with such a large magnitude as a school year, we are trivializing educational findings. On one hand, we magnify small differences. On the other, we attribute large effects to educational policies that are not so effective. And furthermore, we contribute to educational alarmism, since even small differences lead us to speak of “half a school year of schooling” for a distance that in any other area of our lives seems short—“half a school year,” that is, 10 points (0.1 standard deviations), is like comparing a person who is 1.70 m tall with another who is 1.69 m.

For all these problems, it seems more sensible to stick to the well-established criterion in educational research of considering that the effect of a school year is between 0.5 and 0.7 standard deviations. Applied to the PISA metric, this equates to about 50–70 points, more aligned with previous waves, which were around 40 points.

What happened in the latest wave?

One aspect remains to be explained: why the one-year schooling effect has been so devalued. Perhaps because school in-person activity was suspended for weeks: shorter school year, smaller effect.

Or perhaps because structural changes have occurred in how social origin, sex, and immigration influence differences among students. In this case, we attribute to the school only the reduction in differences due to these characteristics between students in one year or another.

In this regard, it should be considered that the students from the 2018 and 2022 waves have completed all their compulsory education after the 2008 Great Recession. It would be necessary to explore whether family impoverishment, as well as cuts in per-student investment, could have affected schooling performance.

While at the beginning of the depressive cycle there is evidence that families compensated for education cuts, as the recession prolonged, it did damage educational quality, either of the schools or of the families (more impoverished and stressed by the crisis).

Source: The Conversation.