October 13, 2025 | National University of San Martín (Buenos Aires, Argentina).

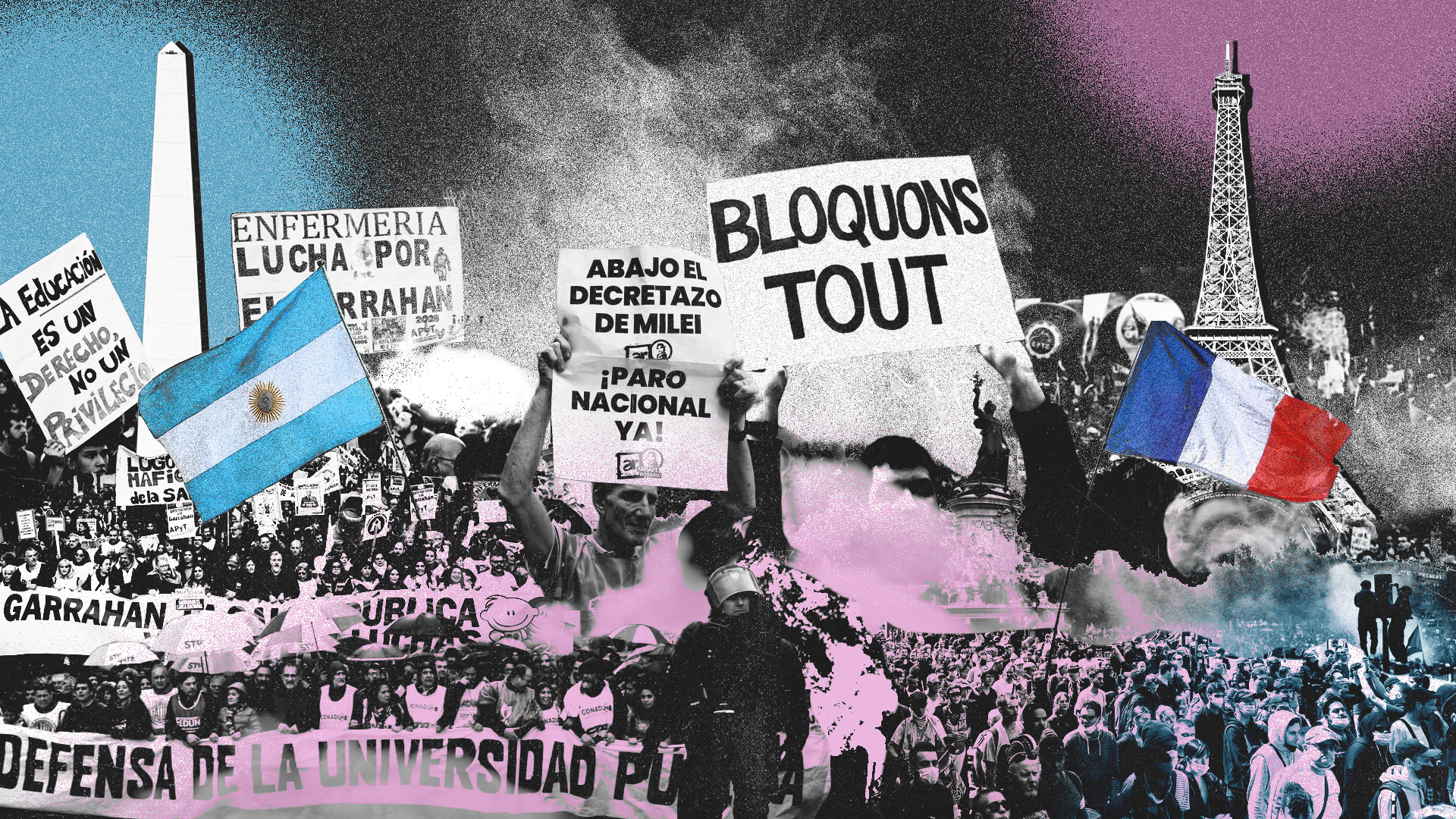

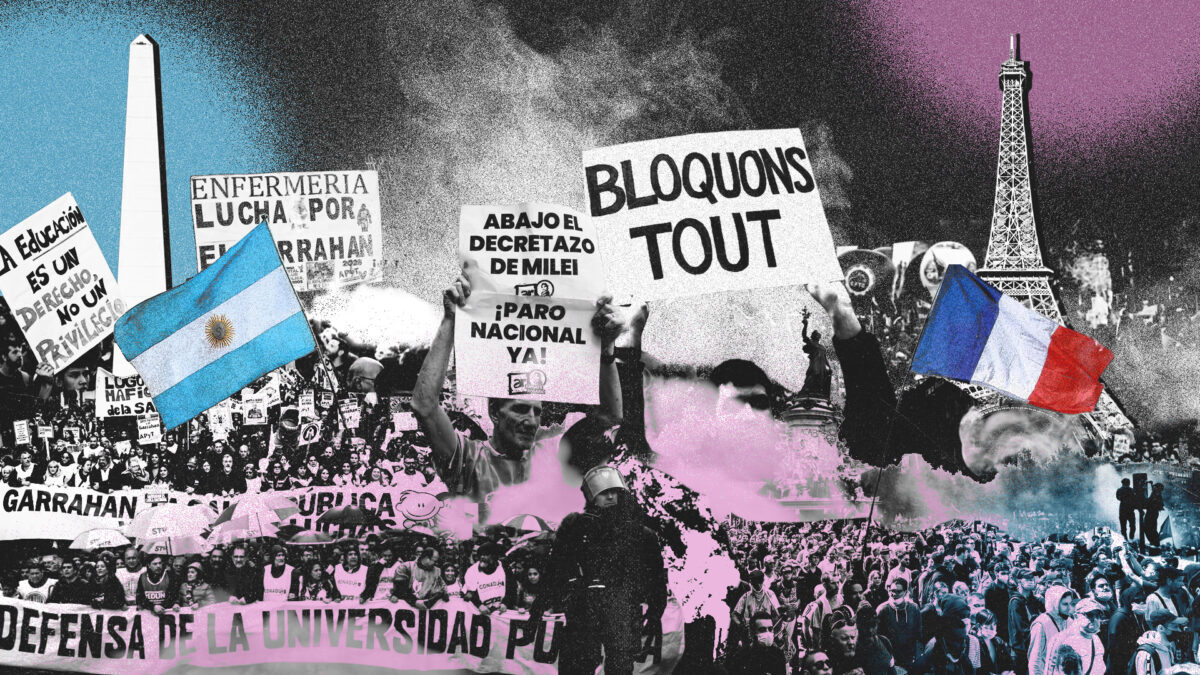

In some way, today’s French society resembles Argentina’s. And it is due to the effect of economic policies that seem obsessed with fiscal austerity but actually implement their strategic plan: channeling capital from public coffers to the private sphere. Social movements, unions, workers on both sides of the Atlantic: how to survive the asphyxiation that brutally cuts access to basic rights.

By: Eduardo Chávez Molina & Emanuele Ferragina

Art: Sebastián Angresano

Sometimes, comparative perspectives are necessary: beyond the weight of traditions that forge unique institutions, in some way, Argentina and France resemble each other today. The economic policies of their governments obsessively target fiscal austerity. They brutally cut the areas that protect the dignity of their inhabitants: health, education, material well-being.

Mark Blyth already wrote about it in Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea: fiscal adjustment policies make austerity operate as a screen that hides a strategic purpose: the massive transfer of resources from public coffers to the private sphere. In France, for example, the data on the evolution of the destination of national income in the form of public aid are eloquent. More than ten years ago households were the main destination of those transfers, but in the following years the change was so radical that today companies are the main beneficiaries of those funds.

The specialized literature calls them “Trinity of austerity“, thus synthesizing the project that consists of continuously transferring resources from the world of work to the owners of capital. This “Trinity of austerity” depends on three interconnected elements:

Fiscal Austerity, which involves cuts in social spending (mainly health and education) and regressive tax reforms, favoring the 1% that benefits from capital gains.

Monetary Austerity, which raises interest rates, harming indebted families, slowing the economy, and undermining workers’ bargaining power, increasing pauperization and unemployment.

Industrial Austerity, which manifests in state intervention in the labor market through deregulation and dismantling of labor and union rights.

Together, these policies seek to ensure the subordination of workers and the unquestionable dominance of the capital order, “the caste”.

In Argentina, Milei has framed the economic austerity plan as the inevitable path the country must face after two decades of “fiscal excesses“. Milei managed to articulate a transversal coalition that backed an unprecedented adjustment: from the classic right to informal workers. The key to the momentary success of the program lay in the distributive consequences of permanent inflation. This caused the Peronist movement, which for decades exercised hegemony over the lowest strata of the population, to see its electoral base erode. However, those who allocate all their income to immediate consumption—many of those informal Milei-voting workers—were the most punished by the constant loss of purchasing power. The most marginal segment of society was largely excluded from these lifelines. Meanwhile, the Peronist coalition managed to maintain electoral support from public workers, and professional classes found their own safeguard in the dollarization of their savings.

From this perspective, the Argentine scenario resembles—even in more extreme terms—the European context, due to the growing frustration of the poorest strata of the population (a kind of invisible majority). Part of it moved away from traditional left parties in Europe or Peronism in Argentina.

Faced with this panorama, Milei burst into Argentine politics with a radical proposal forged in neoliberal ideas applied in Europe after the 2008 crisis: dismantling the state apparatus, eliminating economic intermediaries, and deregulating markets through an austerity shock. The path was presented as the only way to “crush” inflation and, crucially, to neutralize Peronist resistance. In this narrative, the suffering “of privileged groups” for state regulationists transforms into a symbolic gain for the common citizen, similar to discourses in Europe that pit “ordinary people” against “elites“. In reality, the gain is for the country’s large financial and exporting elites. Nothing new on the western front.

On the other side of the Atlantic, in full August, when France was sinking into the lethargy of vacations, former Prime Minister François Bayrou launched a message that resonated strongly: “All political leaders go on vacation, something very well deserved, but this is something I will not do.”

With that statement of intent, almost an austerity oath, he premiered his YouTube channel, FB Direct. An unprecedented format for him, promising to be a direct bridge, without filters or staging, with citizens. The real objective, however, was to defend the unpopular budget cut package presented a month earlier, a bitter remedy for the French economy.

The 2026 budget law, with an unprecedented adjustment of 44,000 million euros, does not limit itself to freezing spending. Its most controversial measures shake everyday life: the suppression of two public holidays and the cut of 3,000 public jobs. Bayrou himself defined it as “a blank year“, a necessary sacrifice to redirect the bloated debt and deficit suffocating the country.

The figures in France are overwhelming: a debt reaching 3.3 trillion euros and a deficit of 5.4% of GDP, well above the 3% target set by the European Union for 2029. Bayrou insisted that this mountain of debt was not a future threat, but an immediate danger. A present that demands, according to his narrative, collective renunciations and constant vigilance, even on rest days.

The arrival of Sébastien Lecornu as François Bayrou’s successor did not alter the political course, but deepened the same measures that had already generated discontent to the point that he was ousted in three weeks, deepening an unpredictable crisis. This triggered a long mobilization of French society, articulated from the grassroots under the slogan “we block everyone“. The movement, of an assembly and popular nature, managed to converge with unions, pro-Palestine youth collectives, and anti-adjustment movements that reject the social impact of migration policies.

In this context, emerging directly from the grassroots—what some today would call from the network—a protest movement has arisen that is difficult to classify using classical categories. It is interesting to note how France has, in recent years, been traversed by social movements opposed to the country’s economic and political elites. The case of “we block everyone” is only the most recent in chronological order and follows other popular movements, from Nuit Debout to the yellow vests.

The roar of workers’ assemblies is fading in twenty-first-century France. Trade unions, once the backbone of labor struggles, are navigating an inexorable decline. Deindustrialization and a labor market fractured by precarious employment and self-employment have eroded their base. The reform of employee representation bodies (Comité social et économique, CSE) diluted their influence, in a context where labor relations have become increasingly individualized. Their strategies, perceived as rooted in the past, no longer resonate in the new workshops of the economy, distancing them from the very workers they claim to represent. A fading echo.

The seed of the call to block France on September 10 traces back to May, when the small sovereigntist association «Les Essentiels», led by Julien Marissiaux—an unusual far-right conspiracy theorist—issued the first slogans through a confidential Telegram channel. Its message, advocating withdrawal from the EU and the defense of the self-employed and Christian roots, initially failed to elicit a significant response.

Aquí tienes la traducción al inglés académico, manteniendo todo el formato original y sin resumir ni truncar el contenido:

The turning point came in July with the announcement of unpopular government economic measures: the elimination of two public holidays, cuts in public services, and reductions in medical benefits. This social discontent found a perfect amplifier on July 24, when a TikTok video by «Les Essentiels» employing the rhetoric of health lockdowns went viral under the hashtag #bloquonstout.

The mobilization then transcended its creators, acquiring an unforeseen dimension. The Telegram channel «Indignémonos» became the organizational epicenter, attracting thousands of users. In an unusual political phenomenon, the movement brought together, since August, figures from both the far right and far left, collectives from the COVID crisis, and former yellow vests. This heterogeneous and unstructured coalition, according to intelligence services, shared social discontent but diverged in its methods, ranging from economic boycotts to the occupation of roundabouts or the demand for a citizen-initiated referendum.

The emergence of “Bloquons tout” constitutes a response to the decline of the trade union movement and the rise of new organizations claiming threatened rights. However, this new form of protest conceals an inherent fragility.

Faced with direct action and viral indignation on social networks, the union endures as an institutional mechanism. Its strength lies not in momentary effervescence, but in the structural continuity that sustains the defense of rights and ongoing negotiation. While anger may dissipate, the trade union institution ensures that demands are not abandoned, offering lasting protection that mere virality cannot replace. Thus, the movement reveals a social malaise, but its challenge lies in overcoming ephemerality.

The public debate on the ‘rightward shift’ (derechización) of French politics and society remains open. While, from an electoral and political standpoint, this shift toward the right appears evident, at the level of social demands the situation is less clear-cut, as demonstrated by the insightful analysis of the French sociologist Vincent Tiberj in his book La droitisation de la societe francaise? Mythe et realité (literally, The Rightward Shift of French Society: Myth or Reality?). Although the baby boomers generation provides significant support for conservative ideas at both social and economic levels, this does not appear to be the trajectory of subsequent generations. The strong social conflict emerging in the country could be partly explained by these differing orientations. With a politics that, from above, continues to impose conservative and neoliberal economic and social measures, while society also raises other types of demands that remain unanswered.

President Javier Milei, with his impulsive and dogmatic stamp, asserts that there is no alternative to economic adjustment because he inherited a bankrupt State, with negative reserves and galloping inflation. His government must implement a fiscal shock—reduction of the State, cuts to subsidies, and public layoffs—as a necessary “chemotherapy” to heal the economy.

He argues that, without this transitory pain, the crisis would worsen. The goal is to eliminate the deficit, lower inflation, and generate confidence for private investment. Milei insists that it is an emergency measure, not ideological, given the lack of funds. His critics, however, point to the high social cost, and there are economic positions that propose alternative paths.

Nearly two years later, the scenario is different, but the message remains the same, polished by time and tempered in the furnace of reality. Milei, now in a dark suit and blue tie, speaks in the tone of a doctor announcing a raw but necessary diagnosis in a recorded message, insisting that “fiscal order and surplus” constitute “the only path” toward Argentina’s prosperity and “the definitive solution” to the problems afflicting the country: it is either vote for progress or Argentina regresses.

Before the string of political blunders and the electoral defeat against Kicillof in the Province of Buenos Aires, he marked a turning point. The message reached every household through a national broadcast: “Increasing public spending is destructive. When a State spends more than it earns, it generates emission, and that produces inflation: a monetary phenomenon that reduces purchasing power”.

The forcefulness of the assertion was as seductive as it was deceptive. In its simplicity, it concealed a reductionist view of the economy, a narrative constructed around a single causal axis—the monetary emission—, deliberately ignoring the complexity that characterizes inflationary processes. There was no room for cost-push inflation, driven by rises in international prices or productive bottlenecks; nor for demand-pull inflation, let alone the role of expectations.

And it is there, in that space of the unspoken, where the theory breaks down. Because inflation is also—and above all—a social and psychological phenomenon. When people expect prices to continue rising, they act accordingly: negotiating wages, adjusting prices, protecting themselves with dollars. Thus, a self-reinforcing circle is created, independent of the amount of money in circulation.

Reducing everything to the money supply is not only a technical error: it is a simplification that ignores painful lessons from the economic history of Latin America. Multi-causality is not merely a vague theory: it is a reckoning of hypotheses.

Under the implacable logic of an orthodoxy that proclaims itself unquestionable, Javier Milei’s government navigates amid scandals that tarnish its narrative of purity. The national broadcast of the Caso Libra—with accusations of an alleged 3% kickback system involving his sister and right-hand woman, Karina Milei—seems to crash against a wall of unshakable conviction.

True to a course set without room for pluralism or pragmatism, the administration insisted on enforcing the veto against funds cut from public universities and allocations for people with disabilities, even after the resounding rejection at the polls on September 7, and then denying them budget despite the limitless search for money to cover the economic debacle, such as the new bailout from the Trump administration. The decision—analyzed by La Nación as one more step into the “swamp of the Province of Buenos Aires”—reflects an almost dogmatic resistance to revising strategies, even in the face of mounting political evidence of wear and tear.

In response to this, two phrases resurface with irony, directly challenging stubbornness in power: the one that warns “only beasts do not change their minds”, and the maxim attributed to Francis Bacon: “He who will not reason is a fanatic; he who cannot think is an idiot; he who dares not think is a coward”.

Both serve as uncomfortable mirrors for a discourse that—trapped in its own swarm of certainties—appears to have obscured its capacity to listen, rectify, or simply think. The harsh and confrontational rhetoric that brought it to power now entangles itself in its own contradictions, while society awaits signs that rigidity has not completely eclipsed reason.

In Argentina and France, the same discourse resonates: the promise of a prosperous future in exchange for an austere present, as demonstrated by the authors in their research at the red INCASI funded by the European Union. It is presented as a necessary sacrifice, a painful but unique path toward economic redemption. However, the cost of this gamble once again falls on the usual suspects: the historically forgotten, those condemned to swim against the current of a system that demands ever greater training to avoid being trapped in exclusion. For them, the “sanctuary of progress” seems aptly named San Jamás—a place one only hears about but never reaches. The promise thus becomes a mirage that perpetuates the very gap it claims to close.

Source: Anfibia Newsletter.