Arnau de Vilanova was the main mastermind behind the movement at the University of Montpellier which, in southern Europe in the late 13th century, led to a major revamping of the studies and practice of medicine through the appearance of Galen’s works and Arab Galenism which had heretofore been unknown in the West. All of this together has been called the “new Galenism” (García-Ballester).

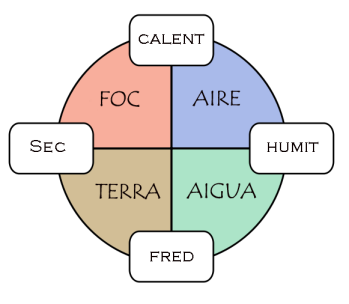

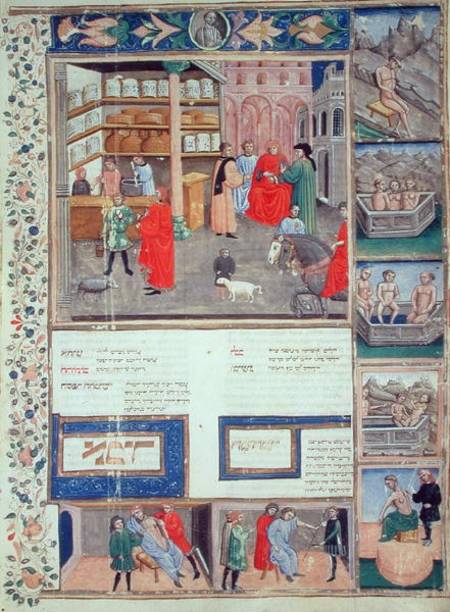

Galen, a Greek physician who had been born in Pergamon and worked in Rome (AD 129-210/216), developed a medical synthesis which was grounded in the Hippocratic tradition, Aristotle and other authors, and in his own clinical and research experience. His extensive oeuvre was the foundation of Galenism, a movement which started in late antiquity which he systematised and conveyed in the guise of a unified doctrine. Galenism became the predominant current in educated medicine until the 17th century. Galenism is grounded upon the philosophical principle that there are four qualities in nature: warmth, cold, dryness and moisture – whose combination gives rise to the four humours in the human body: blood, phlegm, black bile and yellow bile. The majority of illnesses stem from an imbalance in the amount, proportion or quality of the humours. Therefore, the physician’s mission is to restore the lost balance using all the means within his reach. He first resorts to diet, meant as a living regime: it regulates not only the patient’s food but also all his or her daily activities – where he lives, works and exercises, and including bathing habits and sound. The physician then draws from an extensive, complex range of medicines, most plant-based, and he only turns to surgery as a last resort. Another common therapeutic recommendation was bleeding or phlebotomy.

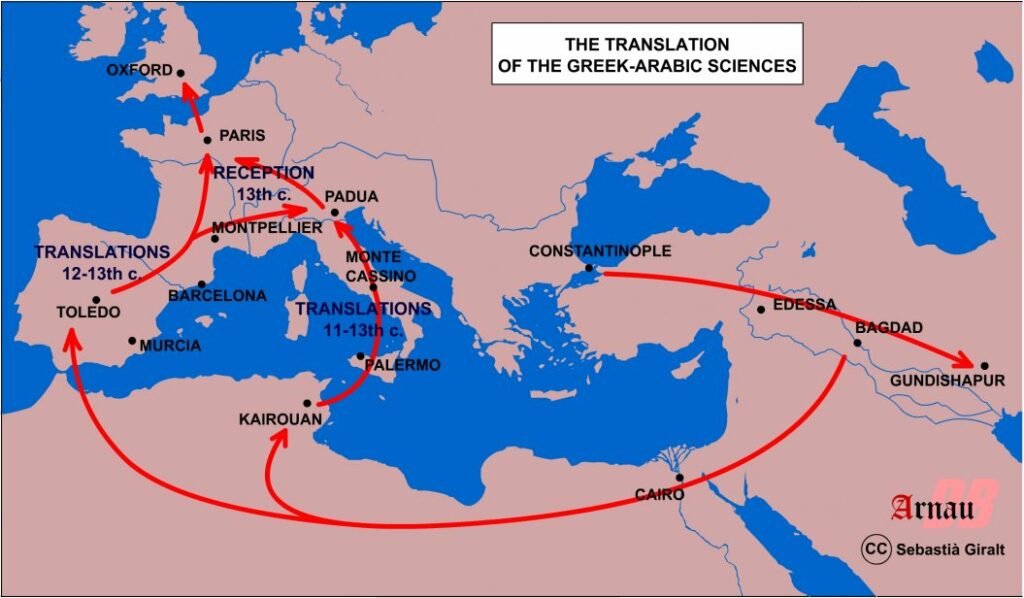

With the fall of the Western Roman Empire, ancient medical knowledge in the west declined, and only the rudiments of it were conserved in the monasteries. The Byzantine world was against Galen. The Nestorians were banished from Constantinople for heresy in the 5th century, first in Syrian Edessa and later from the Persian Gundeshapur, cities where the Greek treatises in the different sciences were translated into Syrian and Persian. When the Muslims conquered the entire Middle East in the 12th century, the Greek sciences, with Eastern influences, shifted to Islam and were translated into Arabic. Thus, in the cosmopolitan, tolerant atmosphere of Baghdad, the sciences blossomed in the Arabic language. However, the Arab intellectuals did not limit themselves to conveying the knowledge of the ancients; rather they often expanded this knowledge with their own contributions. Major medical syntheses were written, such as Avicenna’s Canon and Averroes’ Colliget, which would come to have a major influence in the West.

The routes through which the ancient sciences – natural philosophy, medicine, mathematics, astronomy, astrology – were transmitted to southern Europe were the Italian and Iberian Peninsulas because of their proximity to the Arab world. Italy also benefitted from its contact with the Byzantines. On the Iberian Peninsula, the systematic assimilation of the Greco-Arabic sciences took place in Toledo, where 12th-century Christian intellectuals translated Aristotle, Galen and the great Arab physicians from Arabic and Latin with the help of Jews and Mozarabs. Translations from Arabic also occurred in other places, like the Ebro River valley, Barcelona and Montpellier. Over time, the Greco-Arabic sciences spread throughout all of Europe via the universities which were springing up after the late 12th century. In these new centres of learning, all fields were taught with an Aristotelian foundation, and medicine found a place of its own thanks to which it entered the system of the scholastic sciences and improved its social prestige.